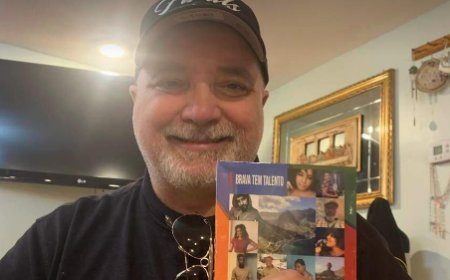

Brushstrokes in the past: Parish of Nossa Senhora do Monte, its origins, its past and its history

(...) Brava Island, the smallest inhabited island in the Cape Verde archipelago, is strategically located in the Sotavento group, in the center of the Atlantic Ocean. Discovered in 1462 by the Portuguese explorer Diogo Afonso, the island has a rich and complex history, marked by waves of settlement, diverse cultural influences and a deep religious tradition. This report aims to meticulously explore the origins and early history of the parish of Nossa Senhora do Monte on the island of Brava, seeking to answer the user's question through a comprehensive historical analysis. Currently, the island of Brava is administratively divided into two civil parishes: São João Baptista and Nossa Senhora do Monte. This division represents a later phase in the island's history, making it necessary to examine the conditions that led to the establishment of the parish of Nossa Senhora do Monte. The existence of two distinct parishes on a relatively small island suggests a significant level of historical development and the potential for different settlement patterns or religious influences in the areas they cover. It is common for small islands to begin with a single central settlement and religious institution. The emergence of a second parish usually indicates population growth, the development of distinct communities in different geographical areas or the influence of specific historical events that have shaped the island's religious landscape.

The discovery of Brava Island took place in 1462 by Diogo Afonso, a Portuguese explorer in the service of Prince Henry the Navigator. This event took place relatively soon after the start of the Portuguese exploration of the Cape Verde archipelago, which began around 1456. Initially, the island was named São João Baptista after the saint whose liturgical feast day (June 24) coincided with the discovery. This naming practice was common among the Portuguese during their era of exploration and colonization, often associating new territories with significant dates or religious figures. The island was later renamed Brava, a Portuguese term meaning "wild" or "brave", possibly in reference to its rugged terrain and dense vegetation. This change of name reflects a transition from a religiously-inspired designation to one based on the island's physical characteristics. The initial religious name demonstrates the strong influence of Catholicism from the beginning of Portuguese involvement with the island. The later change to a secular name like Brava may indicate a growing understanding and characterization of the island based on its physical attributes by the settlers. Portuguese explorers and settlers operated within a worldview deeply intertwined with Catholicism. Naming new lands after saints was a way of claiming them under a Christian framework and invoking divine favor. The subsequent change to a secular name like Brava probably reflects the practical realities of settlement and the perceived characteristics of the island by its inhabitants.

The settlement of the island was delayed, with the first recorded arrival of settlers only occurring in 1573, led by Commander Martinho Pereira. This initial settlement was relatively small. A more significant wave of settlement occurred during the 17th century, peaking around 1680. This substantial increase in population was largely driven by refugees fleeing the devastating volcanic eruption of Mount Fogo on the nearby island of Fogo in 1680, which covered much of the island in ash, making it uninhabitable for many. These settlers came mainly from Madeira and the Azores, with their arrival beginning around 1620 and continuing with the flow from Fogo. The Madeiran connection is particularly important for understanding the potential religious influences. The book explicitly states that the original population of Brava was mostly European and came from Madeira, Minho and the Algarve. Frequent pirate attacks during the 17th and 18th centuries forced the growing population to move to the interior of the island in search of safety, leading to the founding of the town of Nova Sintra around 1700. The significant Madeiran presence from the earliest stages of settlement suggests a strong likelihood that religious customs, including the veneration of specific saints and Marian devotions popular in Madeira, were transplanted to Brava. Late settlement patterns influenced by geography probably played a role in the eventual establishment of distinct communities and religious centers across the island. Settlers tended to recreate familiar aspects of their homeland in their new environment, including their religious practices. Large-scale migration from Madeira, a region with a strong Catholic tradition and specific Marian devotions, would naturally have led to the introduction and spread of these religious elements on Brava. The need for inland settlements due to pirate threats may also have contributed to the development of religious focal points far from the initial coastal landing areas.

Catholicism was the dominant religion brought to the Cape Verde Islands by the Portuguese colonizers, beginning shortly after their arrival in the mid-15th century. The Portuguese Crown actively promoted the spread of Christianity in its overseas territories as part of its imperial project. The initial and ongoing efforts of various Catholic orders to evangelize the archipelago included the Franciscans, who were among the first to minister on the islands, followed by the Jesuits and Capuchin friars. These orders played a crucial role in establishing churches and attending to the spiritual needs of both the European settlers and the enslaved African population brought to the islands. The creation of the Diocese of Santiago de Cabo Verde by Pope Clement VII in 1533 was a crucial moment. Initially, this diocese had a vast jurisdiction, covering not only the Cape Verde Islands, but also parts of the West African coast. The creation of the diocese marked a formalization of the presence and administrative structure of the Catholic Church in the region. The early and comprehensive establishment of the Catholic infrastructure in Cape Verde, including the diocese and the activities of the missionary orders, laid the foundations for the development of parishes on individual islands such as Brava. The close relationship between the Portuguese state and the Catholic Church ensured that religious institutions were an integral part of the colonial enterprise from the very beginning. Portuguese colonization was driven by a combination of economic, political and religious motives. The establishment of the Catholic Church hierarchy and the work of the missionaries were seen as essential for the spiritual well-being of the settlers, the conversion of the indigenous populations (although they did not exist in Cape Verde at the time of the discovery) and the general legitimization of Portuguese rule.

Given that the island was initially named São João Baptista, it is highly likely that the first parish established on Brava was dedicated to this saint, reflecting the initial religious identity associated with the discovery of the island. Although the exact date of foundation remains uncertain in the excerpts provided, its existence as the main parish in the early period of the island's history can be inferred. The Creole Genealogist postulates that the parish of São João Baptista probably came into being as the island's name changed from São João to Brava during the 18th century. This suggests a continuity in the dedication of the patron saint, even with the change in the island's secular name. The availability of vital records (marriage registers) for the parish of São João Baptista from around 1806 provides tangible evidence of its established presence in the early 19th century. The dedication of the first parish to São João Baptista is directly in line with the island's initial name, reinforcing the early religious and cultural influence of this saint on Brava in particular. The subsequent appearance of the parish of Nossa Senhora do Monte indicates a subsequent change or expansion in the island's religious landscape. It was common practice in Portuguese settlements to dedicate the main church and the first parish to the patron saint of the land, especially when the land was named after this saint. The continuity of this dedication even after the island's name change suggests a deep-rooted religious tradition associated with São João Baptista in Brava's early history.

Multiple reliable sources in the excerpts converge on the approximate year of 1826 for the establishment of the parish of Nossa Senhora do Monte. The excerpt from "The Creole Genealogist", with an article last updated in 2014, explicitly states that the parish was established a hundred years after 1726, placing its foundation around 1826. Similarly, the Wikipedia excerpt, last updated in 2020, also confirms the year of foundation as 1826. The consistency between different sources regarding the foundation date of 1826 provides a strong indication of its accuracy. This suggests that the formal religious administration of the island expanded in the early 19th century to accommodate the needs of a growing or geographically dispersed population. The establishment of a second parish on Brava probably reflects an increase in the island's population, potentially concentrated in areas far from the original settlement associated with São João Baptista. This expansion of the religious infrastructure would have been necessary to provide adequate pastoral care and administer the sacraments to the growing Catholic community.

The indicates that Nossa Senhora do Monte became the seat of a bishop a few years after its foundation in 1826. O also supports this, stating that it became the seat of a bishop "a few years later". This elevation, even if temporary or for a specific period, underlines the growing religious importance of this location on the island. However, this needs to be reconciled with the information in the e which states that Brava was the seat of the bishopric and government in 1800, predating the foundation of the parish. This discrepancy requires careful consideration in the final report, potentially suggesting two different periods in which Brava held this distinction or an inaccuracy in a set of sources. The report further complicates this by mentioning the mid-19th century as the period when Brava was the provisional seat of the Bishopric and Government. In 1862, Nossa Senhora do Monte further consolidated its religious importance by becoming a recognized pilgrimage site. This suggests the development of local traditions, beliefs or possibly specific events that attracted devotees to this parish. The village of Nossa Senhora do Monte is geographically situated in the heart of the island of Brava, nestled between mountains. This central location may have contributed to its later prominence. The potential elevation to the seat of a bishopric, along with its subsequent status as a pilgrimage site, meant that Nossa Senhora do Monte evolved into an important religious center on Brava, attracting both local faithful and pilgrims from further afield. The contradictory information regarding the seat of the bishopric requires careful analysis and potentially further investigation. The selection of a parish as the seat of a bishopric often reflects its strategic location, the size and influence of its congregation and the presence of adequate infrastructure. The emergence of a pilgrimage site, on the other hand, usually stems from popular devotion, often linked to specific religious events, relics or alleged miracles associated with the site or its patron saint.

The Creole Genealogist provides a crucial detail, noting that although the parish was established around 1826, the physical church building of Our Lady of the Mount was only completed after 1841. This suggests a period in which the parish existed as a religious administrative unit before having a dedicated permanent structure. However, the presents a conflicting chronology, stating that the church's legacy dates back to the 1860s and that it took 65 years to build. This would place the completion of the church in the 1920s, significantly later than the later date of 1841 suggested by the other source. This discrepancy warrants close scrutiny of the reliability of the sources and the potential for error in the final report. Recent news articles discuss the ongoing reconstruction efforts at the Catholic Church of Nossa Senhora do Monte, highlighting its lasting importance to the community and the involvement of Brava emigrants in its preservation. The discrepancy in the chronology of the church building's construction highlights the challenges of relying on potentially fragmented historical records. More research may be needed to definitively establish the precise dates of construction. The ongoing efforts to rebuild the church underline its continuing importance as a symbol for the Bravense community, both on the island and in the diaspora. Historical records, especially for smaller island communities, can sometimes be incomplete or contain inaccuracies. Divergent accounts of the church's construction may result from different phases of construction, renovations or oral traditions that have evolved over time. The active participation of the diaspora in the reconstruction efforts demonstrates the strong emotional and cultural ties that Bravense emigrants maintain with their homeland and its religious institutions.

The Creole Genealogist reveals a fascinating historical detail: marriage records dating from 1808 to 1811 refer to "parochial Nossa Senhora do Rosario da ilha Brava", translating directly as "parish of Nossa Senhora do Rosário da ilha Brava". This discovery strongly suggests the existence of a Catholic parish dedicated to Our Lady of the Rosary on the island of Brava during the early 19th century, preceding the confirmed establishment of Our Lady of the Mount around 1826. The book summarizes this intriguing discovery, emphasizing the mystery given that contemporary Brava only has the two parishes of São João Baptista and Nossa Senhora do Monte. The lack of current knowledge about a parish of Nossa Senhora do Rosário among the locals adds to this historical enigma. The documented existence of a "parochial Nossa Senhora do Rosario" in official records from the early 19th century presents a significant historical question about the religious organization of the island of Brava during that period. It challenges the assumption of a simple transition from São João Baptista to Nossa Senhora do Monte as the only parishes. The term "parochial" in official records typically denotes a parish recognized within the administrative structure of the Catholic Church. The consistent use of this term for Nossa Senhora do Rosário in marriage records over a period of several years strongly implies its formal existence as a parish on the Brava during that time. This raises questions about its relationship with the later parish of Nossa Senhora do Monte and what may have led to its eventual disappearance from the historical record or its renaming.

The article reports a suggestion by representatives of the Cape Verde National Archives that the "parochial Nossa Senhora do Rosario" could have been a community established by people from a parish with the same name on another island in the archipelago. This hypothesis points to the role of migration in shaping the religious landscape of Brava, with settlers potentially bringing their devotion to the patron saint and the name of their former parish to their new home. The author of "The Creole Genealogist" notes that although there are parishes named after Nossa Senhora do Monte on other Cape Verdean islands such as São Nicolão and Santo Antão, his older relatives had no recollection of there ever having been a parish of Nossa Senhora do Rosário on Brava. This lack of local oral tradition may suggest that this parish was relatively ephemeral or that its memory has faded with time. O also highlights this mystery, referring to the time period of the records (around 1808-1811) and suggesting that this parish of Nossa Senhora do Rosário may have existed between the period when the island was renamed Brava (in the 18th century, after São João) and the establishment of Nossa Senhora do Monte in 1826. This period suggests a possible transition period or a different geographical area of the island served by this previous parish. The most plausible explanation for the "parochial Nossa Senhora do Rosario" is that it represented a distinct community or settlement on Brava, possibly founded by migrants who brought this Marian devotion with them. Its eventual disappearance or transformation into the parish of Nossa Senhora do Monte remains a subject for future speculation and research. The lack of strong oral tradition about this parish could indicate its relatively brief existence or its merger with other religious communities over time. Migration has been a significant factor in Cape Verde's demographic and cultural history. It is conceivable that a group of settlers with a particular devotion to Our Lady of the Rosary established their own religious community and named it after their patron saint or their former parish. The subsequent emergence and prominence of Nossa Senhora do Monte may have led to the absorption or renaming of this previous parish as the island's religious landscape evolved.

The research excerpts provide ample evidence of the significant religious and cultural importance of Nossa Senhora do Monte in other Portuguese-speaking regions, particularly Madeira and Lisbon. In Madeira, Nossa Senhora do Monte is the island's patron saint, with a large annual festival on August 15 that attracts thousands of pilgrims and visitors. The Church of Monte in Funchal is a historic and architecturally significant landmark, deeply rooted in the island's religious identity. Similarly, Lisbon has a Chapel of Nossa Senhora do Monte which offers panoramic views and has historical and religious significance. Given the established historical connections and the significant migration from Madeira to Ilha Brava during its settlement, it is highly likely that devotion to Nossa Senhora do Monte was introduced and gained prominence on Brava through the influence of these Madeiran settlers. Settlers often carry their religious traditions, patron saints and cultural practices to their new homes, and the strong veneration of Our Lady of the Mount in Madeira makes it a likely candidate for transplantation to Brava. The substantial number of Madeiran settlers on Brava since the beginning of the 17th century has created a strong cultural link between the two islands. It is natural to assume that these settlers would have maintained their religious beliefs and practices, including their devotion to important Marian figures such as Nossa Senhora do Monte, who occupies a central place in Madeiran religious life. This cultural transfer probably played a fundamental role in the naming and establishment of the parish of Nossa Senhora do Monte in Brava.

He directly addresses the potential origin of the devotion to Our Lady of the Mount in Brava, quoting a Friar Matias Silva who suggests that it probably came from the island of Madeira in Portugal. He points to the significant component of people from Madeira in Brava's history and notes that the foundation of the parish in the 19th century (around 1826) coincided with a period of strong Madeiran influence. The same excerpt also clarifies an important distinction, emphasizing that Nossa Senhora do Monte is a different Marian title from Nossa Senhora do Carmo. This clarification is crucial for an accurate historical interpretation. The recognition by a local religious figure in Brava of the probable Madeiran origin of the devotion to Nossa Senhora do Monte provides strong support for this hypothesis. It reinforces the idea that cultural and religious exchange between Madeira and Brava played a significant role in shaping the latter's religious landscape. Clarification about Nossa Senhora do Carmo is important to avoid misinterpretations of the parish's dedication. Oral traditions and the perceptions of local religious authorities can often provide valuable insights into the historical development of religious practices within a community. The friar's observation, based on the historical demographic links between Madeira and Brava, strengthens the argument that the name and perhaps the initial impetus for the establishment of the parish of Nossa Senhora do Monte originated from the religious traditions of the Madeiran settlers.

As mentioned earlier, Nossa Senhora do Monte achieved the status of a pilgrimage site in 1862. This development signals a growing local and potentially regional veneration of Our Lady of the Mount on the Brava. The reasons for this emergence as a pilgrimage destination are not explicitly detailed in the excerpts provided, but could be linked to alleged miracles, specific religious events taking place at the site or the church's growing reputation as a place of spiritual significance. The evolution of Nossa Senhora do Monte into a pilgrimage site indicates its growing religious importance and its role in attracting devotees from beyond the immediate boundaries of the parish. This suggests the development of a strong local faith tradition centered on this Marian devotion. Pilgrimage sites often become important centers of religious life, fostering a sense of community among pilgrims and contributing to the local economy and cultural identity. Further research into the specific events or beliefs that led Our Lady of the Mount to become a pilgrimage site could provide deeper insights into Brava's religious history.

The and offer glimpses into the more recent history of Nossa Senhora do Monte, portraying it as a place that once served as an important community center with several essential services, including a post office, banks, commerce, a municipal agency, policing and a health post. These accounts evoke a sense of nostalgia for a perceived "golden age", highlighting the central role that Nossa Senhora do Monte played in the social, economic and administrative life of its residents. Although these excerpts focus mainly on a later period, they suggest that the parish, with its church, would probably have been at the heart of this community life, serving not only as a place of worship, but also as a focal point for social interaction and community identity. The historical presence of various community services in Nossa Senhora do Monte underlines the interconnectedness of religious institutions with the wider social fabric of island communities. The parish has probably played a vital role in shaping community identity and providing a sense of stability and belonging. Historically, churches and parishes often served as central points of organization for communities, especially in smaller, more isolated environments. They provided not only spiritual guidance, but also a venue for social gatherings, community events and sometimes even played a role in local governance and welfare. The memory of Nossa Senhora do Monte as a place with a wide range of services suggests its historical importance as a key center for the island's population.

In short, the parish of Nossa Senhora do Monte on the island of Brava came into being around 1826, probably under the influence of settlers from Madeira who brought with them the veneration of Nossa Senhora do Monte. The previous existence of the "parochial Nossa Senhora do Rosario da ilha Brava", mentioned in records from 1808-1811, remains a historical enigma, suggesting the possible influence of a migrant community. More research is needed to fully understand the history and fate of this earlier parish and its potential relationship with Nossa Senhora do Monte. In conclusion, the parish of Nossa Senhora do Monte has an enduring religious and community significance on the island of Brava, as evidenced by its later status as a pilgrimage site and its historical role as a key hub for the surrounding community. Ongoing efforts to preserve its church building further attest to its enduring importance in the hearts of the Bravense people.

Table 1: Chronology of the Main Events in the History of the Parish of Nossa Senhora do Monte and in the Religious Development of Brava Island

|

Year/Period |

Event |

|

1462 |

Discovery of Brava island, initially called São João Baptista. |

|

1573 |

Arrival of the first settlers. |

|

About 1620 |

Arrival of settlers mainly from Madeira and the Azores. |

|

About 1680 |

Significant increase in population due to volcanic eruption in Fogo. |

|

About 1700 |

Foundation of Nova Sintra in the interior of the island. |

|

About the 18th century |

Probable establishment of the parish of São João Baptista, reflecting the initial name of the island. |

|

1800 |

Brava briefly serves as the seat of the bishopric and government of Cape Verde. |

|

1808-1811 |

Marriage records mention the "parochial Nossa Senhora do Rosario da ilha Brava", indicating a possible previous parish. |

|

About 1826 |

Formal establishment of the parish of Nossa Senhora do Monte. |

|

After 1841 |

Completion of the building of the church of Nossa Senhora do Monte (approximate date). |

|

1862 |

Our Lady of the Mount becomes a recognized pilgrimage site. |