Political representation in Cape Verde, between Mirceas and Damiões, the Parliament we have and the Parliament we could have

Nova Sintra City, November 14, 2025 (Bravanews) - The phrase "If the National Assembly had more Mircea's Delgado defending the interests of the people instead of the parties, we would have fewer Damião's Medinas" sums up a sentiment that is increasingly present in Cape Verdean public debate: the deep wear and tear of traditional party representation and the perception that Parliament, instead of being the ultimate space for democracy, has often become a stage for internal obedience, sterile rivalries and political careers disconnected from the real needs of citizens.

In Cape Verde, as in most countries with a parliamentary system, MPs are elected by closed lists controlled compulsorily by the parties. This means that the MP owes his election much less to the voter and much more to the party that put him on the list, priority loyalty tends to be "upwards" (the party leader) and not "outwards" (the electorate) and voting discipline, which is often automatic, creates a Parliament that is not very diverse in thought and poor in individual political courage.

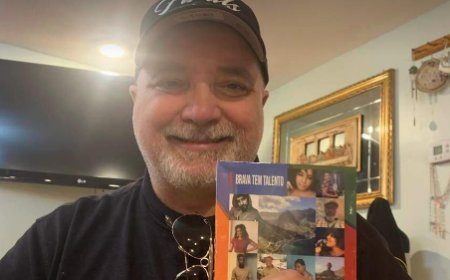

The result is what many Cape Verdeans identify today as an Assembly where few voices stand out for their independence, combativeness and commitment to concrete causes, making figures like Mircea Delgado exceptions in a sea of discreet, silent deputies or those totally aligned with higher orders.

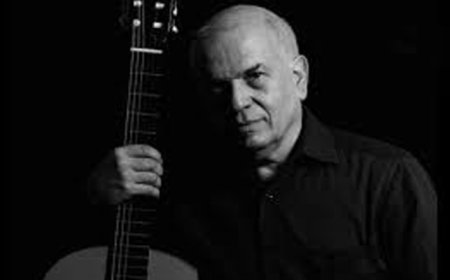

The reference to "Mircea's Delgado" as a symbol of integrity and political courage contrasts with "Damião's Medinas", an expression that evokes figures seen as excessively partisan, lacking transparency or disconnected from the population.

This contrast highlights two ways of exercising the mandate. The MP who questions, monitors and confronts the system, taking positions even when they displease his own party, speaks on behalf of concrete causes and not just the party agenda and is recognized by the people because he is present, active and visible in social struggles.

The MP who follows, protects and reproduces the party machine, acting as a messenger for the party, not as an advocate for the voter, avoids internal conflicts in order to preserve positions, benefits or future electoral invitations and puts internal stability above public responsibility.

The more the latter predominate, the further Parliament moves away from its essential mission, that of representing society and supervising the government.

The way the system is designed creates a serious consequence where people stop believing in parties and, by extension, stop believing in democracy.

In Cape Verde, there has been a clear increase in electoral abstentionism, a feeling of abandonment, distrust in institutions, a perception of impunity and a lack of accountability, and indignation against MPs who only appear at election time.

The population feels they are speaking, but the powers that be don't listen. And when it does, it rarely acts.

Voting for people and not parties - a possible alternative?

The idea of moving from a closed party list model to a personalized or mixed election model is not new and has been applied in several countries.

Portugal has been debating single-member constituencies for years, the United States, France and the United Kingdom elect representatives directly by name, Germany combines party voting with personal voting in a mixed system.

What changes with a person-centered system? The MP must now win the vote directly from the voter, the relationship of proximity increases, individual accountability also increases and MPs become less dependent on parties and more dependent on public trust.

This automatically reduces the number of invisible or merely obedient politicians.

If Cape Verde adopted a system that was more person-centered and less acronym-centered, there would be more parliamentary independence - deputies who vote based on conscience, arguments and the needs of the region they represent, greater connection between voter and elected - the deputy would have to answer to the people and not to the party, real political renewal - it would open up space for competent citizens, community leaders, young people, technicians and voices from civil society, fewer party caciques - the parties would no longer completely control who gets into the Assembly or not, and better oversight of the government - because there would be fewer automatic votes and more qualified debate.

The parties would be unlikely to give up their control over the lists and over Parliament, because that would mean losing power, i.e. the reform will not come from within the system, but from social pressure, public debate and citizen mobilization.

If there were more MPs like Mircea Delgado - independent in their thinking, firm in their oversight, close to the people - and fewer examples of political careerism or party subservience, Cape Verde would have a stronger, bolder and more useful Parliament for democracy.

And perhaps the most important sentence of the whole reflection is this, "It's time to change the vote for parties and make it about people."

The country we want requires a new political model, where integrity is worth more than party color and where competence weighs more than internal discipline.

This change doesn't just depend on politicians. It depends above all on the citizens - on voting, on demanding and on the collective courage to ask for a Parliament of the people and not of the parties.