The industrial complex of poverty and the erosion of the social fabric of Brava Island

(...) Brava Island, often described as the "island of flowers" for its natural charm and rich cultural heritage, is currently facing one of the greatest challenges in its recent history: the erosion of its social fabric. Beyond the well-known structural difficulties—such as emigration, geographic isolation, and lack of investment—an internal phenomenon is also growing that threatens to undermine the community's ability to reinvent itself and move forward. This is what some call the "pity-industrial complex," a deep-rooted culture of victimization and dependency that has weakened social cohesion and the spirit of initiative on the island.

The term refers to a collective mentality that transforms victimhood into a permanent identity. Instead of being a starting point for mobilization and self-improvement, the "poor thing" status becomes a way of life, almost a symbolic industry, where the discourse of incapacity and disadvantage is constantly reproduced, both in political debates and in everyday conversations.

On Brava, this stance is often justified by the island's physical isolation, poor maritime connections, and lack of major government investment. However, when victimization becomes a habit, it ceases to be a tool for legitimate protest and becomes an obstacle, paralyzing action, generating conformity, and preventing the development of individual solutions.

The most visible result is the erosion of community trust. People increasingly view each other as competitors for scarce opportunities rather than as partners for cooperation. Defensive individualism grows, while sustainable collective initiatives diminish.

Another impact is the weakening of the island's youth, who, instead of being inspired by the tradition of courageous and enterprising Brava residents who emigrated and succeeded elsewhere, often absorb this discourse of incapacity, believing that "nothing can be done on Brava." This pessimism fuels early emigration and the abandonment of the island, accelerating population aging and, consequently, a loss of dynamism.

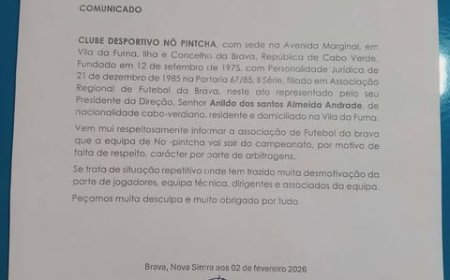

Community associations, which in the past played a vital role in mobilizing for public works, cultural events, and mutual support, are also not immune to the impact. Many are corroded by internal divisions, personal disputes, and a certain civic fatigue, reflecting this logic of collective victimization.

Political discourse in Brava has also been affected. Instead of discussing concrete projects and development paths, the focus often falls on constantly denouncing shortcomings, as if enumerating the problems were enough to solve them. This constant narrative of abandonment generates momentary indignation, but rarely mobilizes transformative energy.

In practice, a cycle is created: the more the idea that Brava is "forgotten" is repeated, the more citizens resign themselves to the idea that it is not worth fighting for change, further reinforcing inaction.

Brava Island has a history of resilience and creativity in its DNA. It is the land of emigrants who, with limited resources, made their way in countries like the United States and maintained a transnational network that still supports the island today. It is also an island of artists, poets, and musicians who have left their mark on Cape Verdean identity. It was the seat of the colonial government, had schools for ship captains, and accomplished much more. This tradition of strength and resilience cannot be obscured by the "pity-industrial complex."

To reverse this trend, it's necessary to revalue collective self-esteem and invest in projects that unite the community around clear and tangible goals. More than just complaining about neglect, it's important to reinvent our way of being: reclaiming the spirit of collaboration, supporting young people with training and innovation, investing in agriculture, fishing, and livestock, energizing associations, and demanding that local and national politicians not just talk, but also deliver verifiable commitments and concrete results.

The erosion of the social fabric on Brava is not inevitable. But to stop it, we must break with the logic of victimhood as a collective identity. The island's future depends not solely on the state or the diaspora, but above all on the ability of Brava residents to unite, value their heritage, and believe in their own potential. Otherwise, the "pity-industrial complex" will continue to silently erode social cohesion, leaving the island increasingly fragile and dependent.