Among the clouds of Brava, Cova do Touro is born at the forefront of the island's brandy industry

We mentioned Césaria Évora, the voice of sodade, the nostalgia that permeates these islands, which the philosopher of Négritude, Leopold Sédar Senghor, called "a garland of happiness mixed with the sweetness of Sunday", but which are perhaps more like "ten grains scattered by God in the middle of the sea". It is to the sound of the poignant notes of Césaria's songs that we arrive at the second stage of our journey, the smallest of the archipelago's inhabited islands, the eternally foggy island of Brava.

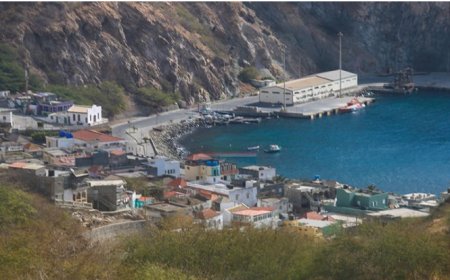

Getting there isn't easy. You have to fly to Fogo, a sublime lava cone with lunar landscapes where people live and cultivate vineyards in the caldera of Pico do Fogo, an active volcano. From there, a two-hour boat ride through schools of dolphins and flying fish takes you to the small port of Furna. Seen from the sea, this rock with 5,000 inhabitants seems to be shrouded in a hat of permanent clouds. When you reach Nova Sintra, the main town in the heart of the island, covered in an almost metaphysical mist, you get the feeling of being in a place outside time and space.

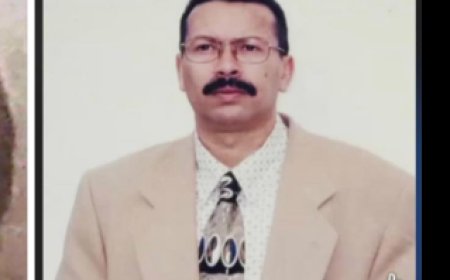

The story of Brava is told to us by Daniel Miranda, known as the Bull, whose tense muscles and wide smile give him the look of a rock star. Sitting at the table to taste totoco, a typical local dish, we learn that Brava is the greenest, coolest and rainiest island in the archipelago, which is why he chose to grow sugar cane here. But rain, of course, is not in itself a source of wealth and Brava was gradually depopulated over the course of the 20th century. Generations of young people emigrated to the United States, helped by contacts with whaling crews. The whaling industry is also responsible for the name that the Bravenses give to cane brandy.

"When, at the beginning of the 20th century, English and especially American ships began passing through Brava on their routes," explains Daniel, "the sailors would invade the bars and order whisky, especially blended whisky of a specific brand - J&B."

Since then, in one of those incredible twists of language, J&B has come to mean any spirit. Pronounced in the local way as djabì, it ended up designating the agricultural rum produced on the island.

Fascinating stories, sad tales of farewells and dreamed-of returns can be found in the lyrics of morna, the music of Brava, sung by Césaria Évora. Listening to it live is the height of melancholy, but it helps to understand the cultural substratum of a place where Portuguese conquerors, fugitives from French pirates and whalers from New England crossed paths for centuries, all united by a common element:

"Aguardente was a stimulant for work, a nectar at parties, a remedy for any illness."

Daniel is the largest landowner in Brava, but he also buys sugar cane from other producers. His distillery is called Cava do Touro - the bull, of course, being Daniel himself - and was built on a hill surrounded by clouds, agriculture's best friend.

It all started when Daniel was a student in Praia and returned to visit his family, living with djabi producers and learning from them. A pharmaceutical technician with an interest in chemistry, he fell in love with agriculture and distillation.

"Initially, djabì was only produced on the coast, in Tantum Bay, because seawater was used to cool the stills," he recalls.

Those were difficult times - with no paved roads, people carried the brandy in 20-liter drums on their heads. 25 years ago, production began to take place in a more organized way - to call it "industrial" would be an exaggeration. The process begins with the sugar cane, again white and black. White cane has a Brix level of 16-17 and Daniel only uses it for liqueurs. Black cane reaches 20, is the most expressive and is grown on more than 40 hectares. The two varieties are milled and distilled separately, but both are harvested five months a year, from January to May.

The milling is done in a diesel-powered mill made in Brazil and the juice is transferred to the fermentation vats via an electric system. This is where the second stage takes place, again with natural yeasts and fermentation takes between 6 and 12 days. A temperature of 20°C is enough to start fermentation, but the four 4,000-liter tanks - three more are on the way - can also be electrically heated if the weather is too cold.

In Cava do Touro there are two distillation rooms with two 600-liter Portuguese copper stills, producing 120 liters of djabì each, with a yield of around 20%.

One of the main problems with distillation is the availability of water for cooling. Daniel built a 50-ton tank that collects rainwater and refills itself after it has been used to cool the coil. By the way, a curious detail: a glass window allows you to see the coil submerged in the water.

"I made this for the schoolchildren! When they come to visit, it's good for them to see for themselves how the still works," smiles Daniel.

If the "heads" are cut to the traditional 3-4%, the definition of the alcohol content of the djabì when it leaves the still is quite unique. "21 grados cubierto", says Daniel, to everyone's amazement. An additional explanation is required: "On the Brava it's practically impossible to find a traditional alcohol meter, everyone uses the Cartier scale." The situation gets complicated: introduced in 1771, the Cartier scale measures the density of an alcoholic liquid at 10 degrees Réaumur - an octogesimal scale where zero is the melting point and 80 the boiling point of water. "21 grados cubierto" means that the djabì must be at least 22 degrees Cartier, or 48% alcohol by volume (ABV) on the Gay-Lussac scale.

Each distillation is different, so after a period of rest, the brandy goes through a blending phase to ensure greater consistency.

The last stage is aging, which Daniel has only recently begun to explore with interesting results. Behind the distillery, among the greenery, a cellar houses several ex-Madeira barrels that he has filled with his djabì.

The result is extremely interesting, as the wood seems to soften the natural strength of the drink, which is definitely more robust and direct than grog. Production reaches 10,000 liters a year, 90% of which is exported to the United States.

The personalized bottlings deserve a separate mention. Available on request at the distillery, they belong to a different category of products, including punches and liqueurs made from white cane and local fruits such as oraça and pitanga. Variations, improvisations on the theme of djabì, the brandy that flows from the still like the tears of those who have left the Brava and dream of returning to its clouds.

Part of the text taken from the original at the link : https://www.velier.it/en/capo-verde/7863-still-tears-that-make-cape-verde-smile.html?fbclid=IwY2xjawP54jJleHRuA2FlbQIxMABicmlkETFKM3JWVVlMUVB4dTRsaE1pc3J0YwZhcHBfaWQQMjIyMDM5MTc4ODIwMDg5MgABHie92ktr778JHfYNRtZNH5-jj05ue-tIZBco2OkrZ01s-9y6BRJcKroA9pmi_aem_H9sd4S5oF5juuYtLVN4aMg